For over 40 years, Butterworth Laboratories has provided independent, contract analytical services to the global pharmaceutical and related industries.

Brewing Chromic Acid: Dennis, GC Liners, and How Lab Safety Changed Forever

3 February 2026

A First Job, a Great Mentor (1991)

It was 1991, and I had arrived at Berridge Environmental Laboratories in Chelmsford, hot off the train from Edinburgh, where I had just completed a 5-year joint honours degree. As shared in previous Blogs, I was being mentored by Dennis, a semi-retired elderly gentleman with a shock of white hair and asbestos fingers from all his years of handling hot GC components. I quickly learned that Dennis always passed on his knowledge of the art with a memorable question, statement or catchphrase which aided learning.

Do We Still Use Chromic Acid?

Recently, I happened to be thinking about safety in the lab, where I am seldom found these days, and asked one of the GC team if we still used chromic acid? This raised an eyebrow, elicited a slight smile, and prompted a “what?” From behind me came the voice of one of the older team players saying, “Frank, your old in-house recipe was forgotten at least 15 or 20 years ago due to safety concerns and as a time/cost saver. As often, I reminisced about my early training with Denis, and I could almost hear his words. “Cleanliness is next to godliness when injector liners are involved, Frank”. Denis would only use GC liners made of quartz crystal rather than glass, and when a new batch of cleaning reagent was needed, he would “brew” the chromic acid. He would put a 5L beaker atop the largest electronic stirrer heating block we had, followed by the addition of a whole Winchester of conc. sulphuric acid, which was stirred and heated until hot. Potassium dichromate was then added in about 10-gram increments until the solution was saturated. This was then left to stir for 10 minutes, then cooled. As the mixture cooled, unreacted dichromate would precipitate from solution, requiring filtration through GFC filter paper, leaving beautiful rust-coloured, particulate-free chromic acid. I always remember the final step when Denis said “and just to give it a little more bite” as he added just a little conc. nitric acid to the final product.

Cleanliness and Quartz: Dennis’ Gold Standard

Dirty liners would be placed into 40mL Teflon-sealed EPA vials filled with chromic acid and left to “clean” overnight. Liners were then well rinsed with purified water and silanised. Quartz wool was then added as required: the first 1/3 was tightly packed to ensure mixing of the injected sample/carrier gas, followed by the remaining 2/3 loosely packed to “wipe the needle” after injection. After packing, a second cycle of silonisation was performed to account for any active sites resulting from breakage of the quartz wool, which may have occurred during packing.

From Brewed Chemicals to Disposable Consumables

Now, of course, chromic acid is purchased from suppliers, not prepared in the lab, and pre-packed, siliconised glass liners are considered disposable items. But I will always remember the cheeky smile on his face as Denis added the final aliquot of conc. nitric to his brew…………

I have added a short discussion of current uses etc. of chromic below if you are interested.

Chromic Acid Today: Uses, Decline, and Regulation (1990–2025)

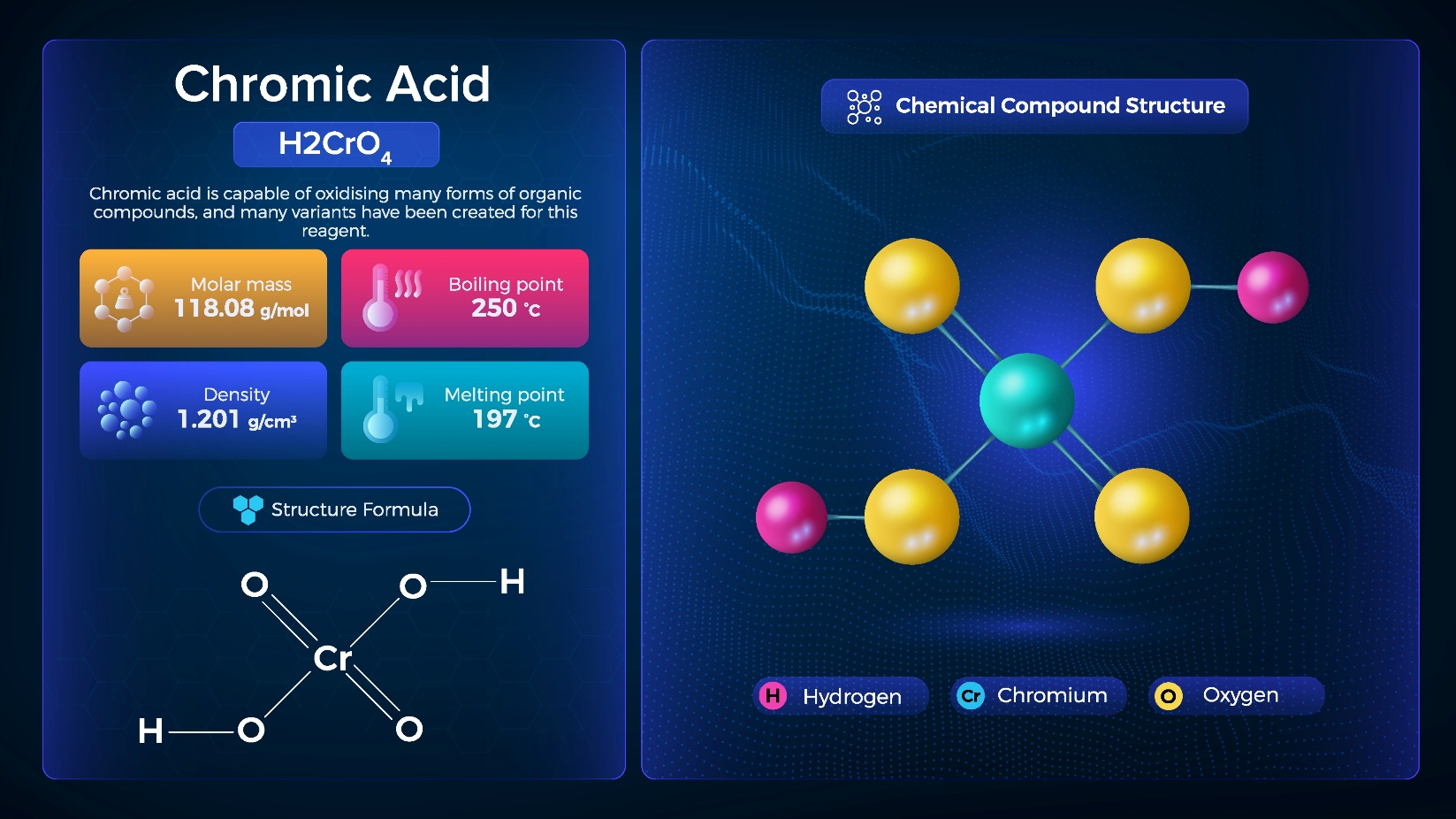

Chromic acid, primarily produced through the oxidation of chromium (III) compounds, has been an essential chemical in various industrial processes since its discovery. From 1990 to 2025, the production and use of chromic acid have been influenced by changing regulatory frameworks, technological developments, and shifts in industrial demand.

In the 1990s, global production of chromic acid was strong, driven by its wide applications in industries like automotive, aerospace, and electronics for chrome plating. It was also used extensively in the leather tanning, textile dyeing, and wood preservation industries (Sullivan et al., 1993). However, as awareness of the toxicity of hexavalent chromium grew, environmental concerns began to reshape its use. Regulatory measures, such as the introduction of the European Union’s REACH regulations and the U.S. EPA’s stricter standards on chromium emissions, started to reduce demand in the early 2000s (Cohen et al., 2005).

In the 2010s, chromic acid production declined in certain regions due to increasing adoption of trivalent chromium alternatives in the plating industry. Despite these changes, chromic acid remained important in sectors such as defence and aerospace, where its exceptional corrosion resistance is critical (Sack, 2010).

By 2025, production figures stabilised, with a shift toward more sustainable chromium recycling technologies, even as the compound’s use in high-performance applications such as aviation remained steady (Dushman, 2020).

While alternatives gained ground, and production has consistantly fallen, chromic acid has maintained its significance in specialised applications, ensuring steady demand amid evolving industrial practices and environmental constraints.

References

- Cohen, M., et al. (2005). The regulation of chromium in industrial use. Journal of Environmental Chemistry.

- Dushman, G. (2020). Chromium recycling and its applications in modern industries. Journal of Industrial Chemistry.

- Sack, J. (2010). The aerospace industry’s reliance on chromium-based chemicals. Aerospace Journal, 12(4), 78–90.

- Sullivan, G., et al. (1993). Industrial applications of chromic acid in metal finishing. Industrial Chemistry Review, 18(2), 112–119.